The Weird Symptom

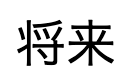

Take the character pair “将来”.

Unicode:

\u5c06\u6765

Chinese users report seeing the Japanese glyph for “将”:

Japanese users report seeing the Chinese glyph for the same character:

What users expect:

- Chinese users want the Chinese glyph.

- Japanese users want the Japanese glyph.

Why are the two groups seeing the “wrong” character?

Unicode Is the Culprit

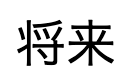

Look at these two screenshots:

The characters (half Japanese, half Chinese) look similar yet not identical. They all share one thing: the same Unicode code point, despite differing glyph designs.

Only a small subset of characters behave this way. Nobody has ever complained about “おはようございます” showing Chinese glyphs.

What is Unicode?

In short, it’s the global standard that assigns a unique code to nearly every character used in written languages.

How Browsers Render Text

Back to the “Chinese glyphs look wrong” problem. To fix it we need to understand how browsers render text.

When the browser encounters a character, it sees its Unicode code point first.

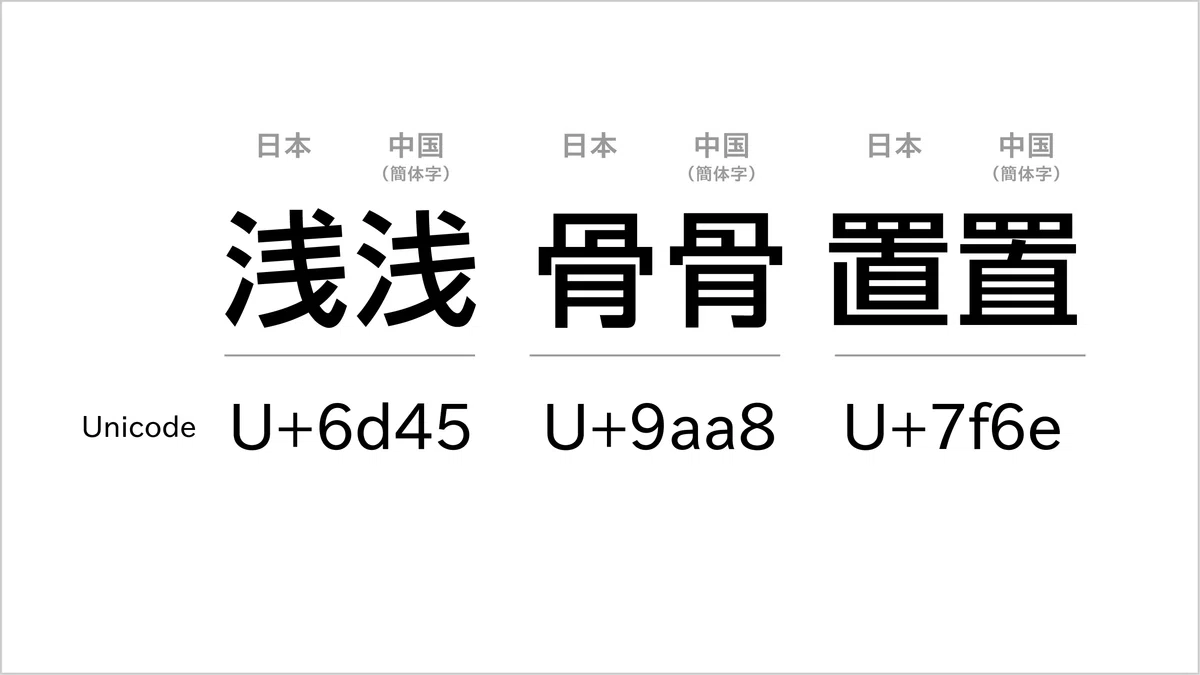

Take the highlighted character.

Take the highlighted character.

When the browser sees U+6D45, which shape should it render?

There are multiple possibilities. The active font determines the shape.

A font file is essentially a map from Unicode code points to glyph outlines.

Operating systems ship with many fonts, and websites can load web fonts.

Common Chinese fonts:

- PingFang

- KaiTi

- SimSun

- Microsoft YaHei

Common Japanese fonts:

- MS 明朝、MS ゴシック

- メイリオ、EPSON 教科書体M

- ヒラギノ角ゴシック

If you render “浅 (U+6D45)” with a Japanese font, you get:

With a Chinese font:

So the naïve fix seems obvious: assign different fonts to Chinese and Japanese users. That would work—but it might be unnecessary.

Browsers can handle this on their own. They can detect the user’s language and pick an appropriate font.

The catch: only if developers have not set a specific font (

font-familyis empty) or only set a generic family (serif, sans-serif, etc.).

How does the browser decide the language?

- It first looks at the page’s

langattribute. If it’s missing… - It falls back to the system language.

From my testing, the browser’s “preferred language” setting is not used here.

So Fix #1 (not ideal) is:

- Don’t set a specific font (generic families are fine).

- Don’t set the HTML

langattribute, so the browser follows the OS language.

That works: Chinese users on a Chinese system see Chinese glyphs, and Japanese users on a Japanese system see Japanese glyphs.

In reality, though, the lang attribute is often necessary—especially when your product supports multiple locales and users can switch languages. When a user switches to Japanese you not only change the text but should also set lang="ja" to ensure these special characters render properly. Otherwise the interface might switch to Japanese, but user-generated text will still show Chinese glyphs because the system language is Chinese.

Therefore, the better option is to set the HTML lang attribute based on the browser’s language when the page loads:

document.documentElement.lang = navigator.language || navigator.userLanguage;

And update it whenever the user changes languages.

The best fix is: dynamically set lang=... according to the browser locale or the language selected in your interface.

Font Fallback

- Some Japanese fonts contain only Japanese characters and almost no Simplified Chinese glyphs.

- Others include both Japanese and Simplified Chinese glyphs (but the overlapping characters use Japanese shapes).

- Chinese fonts behave similarly.

If a page uses a Japanese font that lacks Simplified Chinese glyphs, but the text contains one of those characters, what happens? The browser walks down the font list until it finds a font that includes the Unicode code point.

The downside: fallback often leads to visual mismatch—different characters rendered in different fonts.

(The screenshot below just shows multiple Chinese fonts mixed together to demonstrate how jarring fallback can be. It’s not specifically a Chinese/Japanese example.)

Understanding fallback helps us see that it’s unrelated to the Chinese/Japanese mix-up. Fallback affects visual harmony, not correctness.

Font fallback influences aesthetics, not whether the “right” glyph is displayed.

Common Questions

If the frontend never specifies a font, will the problem disappear?

Not necessarily. The key is setting the correct lang attribute, not the font list.

Will web fonts fix it?

No—same reason.

Can we just pick a Japanese font and call it a day?

No. That would force Japanese glyphs on everyone, frustrating Chinese readers. The reverse (always using a Chinese font) is equally bad.

If you want pretty language-specific fonts, do it after you’ve set lang correctly. Then you can add CSS like:

html[lang='ja'],

html[lang='jp'] {

font-family: /* Japanese font */;

}

/* Covers zh, zh-CN, zh-TW, zh-HK, zh-Hant, zh-Hans, etc. */

html[lang^='zh'] {

font-family: /* Chinese font */;

}

Notes:

- Lumping Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, and Cantonese together isn’t entirely accurate—those locales have their own glyph differences.

- The root cause isn’t unique to Chinese and Japanese. Any time two languages share Unicode code points but design different glyphs, the same issue appears. Latin alphabets run into it as well.

Related Facts

PingFang SC is a Chinese font that also includes Japanese characters, but for the shared code points it uses Chinese glyphs.

Japanese writing combines:

- Kanji

- Hiragana and katakana

- Latin letters

Kanji originate from Chinese characters, but Japanese designers altered some of them over time, so the shapes—and sometimes meanings and pronunciations—diverged.